From 'Survivors of Colonization' to 'Kings and Queens of the Diaspora,' Montclair Art Museum presents Black Joy and Leisure in a Major Exhibition

Home and House for Marion S. Buchanan.

It’s an all-star lineup of artists’ names, from Faith Ringgold and Howardena Pindell to Emma Amos, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Willie Cole, Bettye Saar, Joyce Scott… 59 in total! These are among the best of the best of contemporary artists, who just happen to be Black. And who just happen to be in the collection of the Montclair Art Museum.

Century: 100 Years of Black Art at MAM, curated by Adrienne L. Childs and nico w. okoro, includes 70 works from the museum’s collection, proud proof of the museum’s longtime commitment to the appreciation of Black artists.

It’s organized in sections, and I found myself drawn first to Black Joy and Leisure. In “Po’ch Ladies,” William Edmondson renders two doughy bodies in limestone. The ladies are reclining, arms folded over their chests. They’ve put in a full day – perhaps a lifetime of full days – and are here for a much-deserved moment of respite. One can almost hear their signs. And while porch ladies are known to engage in inspired chatter, these ladies seem content to just rest.

Edmondson, born to freed slaves in Tennessee in 1874, was the first Black self-taught artist to have a solo exhibition at MoMA in 1937.

I found myself circling the vitrine encasing “Home and House for Marion S. Buchanan” looking for the front door. A small model made of scrap wood, metal, washers, nuts, and fabric takes the form of a house and is said to refer to artist Beverly Buchanan’s beloved adoptive mother. “I consider my shacks portraits,” the label quotes her as saying. “It’s the spirit that comes through the forms.”

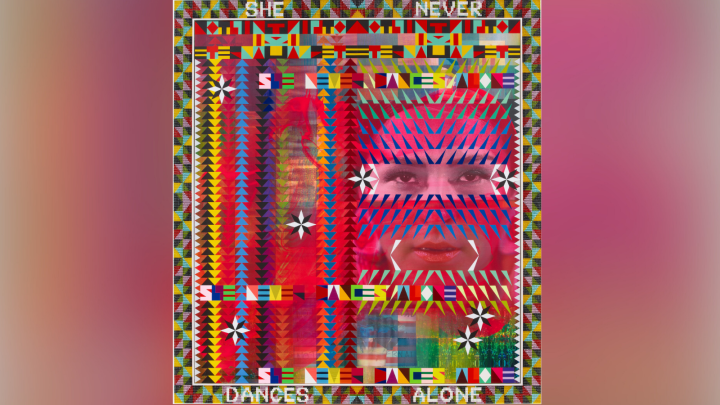

Chit Chat and Apple Martinis. Carmen Cartiness Johnson

Also in the category of Black Joy and Leisure is “Chit Chat and Apple Martinis” by Carmen Cartiness Johnson. This aerial view of a group of friends in a bright yellow room shows them enjoying camaraderie over the aforementioned beverage. “Art should break boundaries and challenge rules,” says Johnson. It should not “require the viewer to have academic education in order to understand.”

Johnson is a self-taught artist who “rejects the politics of respectability imposed by Western standards of beauty and decorum,” according to the curators. She depicts “moments of radical Black leisure – people reading books, enjoying cocktails, lounging on a stoop, dancing at a party, sharing a family meal, chatting in the yard.” I want to join them! I want to hear the conversation!

Artist Janet Taylor Pickett uses Henri Matisse’s iconic “The Red Studio” as a jumping-off point for a series of hand-colored etchings exploring her own life, from childhood, family history, the importance of home, African art, and domestic interiors.

She also builds upon the collage work of her predecessor Romare Bearden, whose “Late Afternoon” – just down the wall – also incorporates images of people engaged in rituals of life, employing photo fragments.

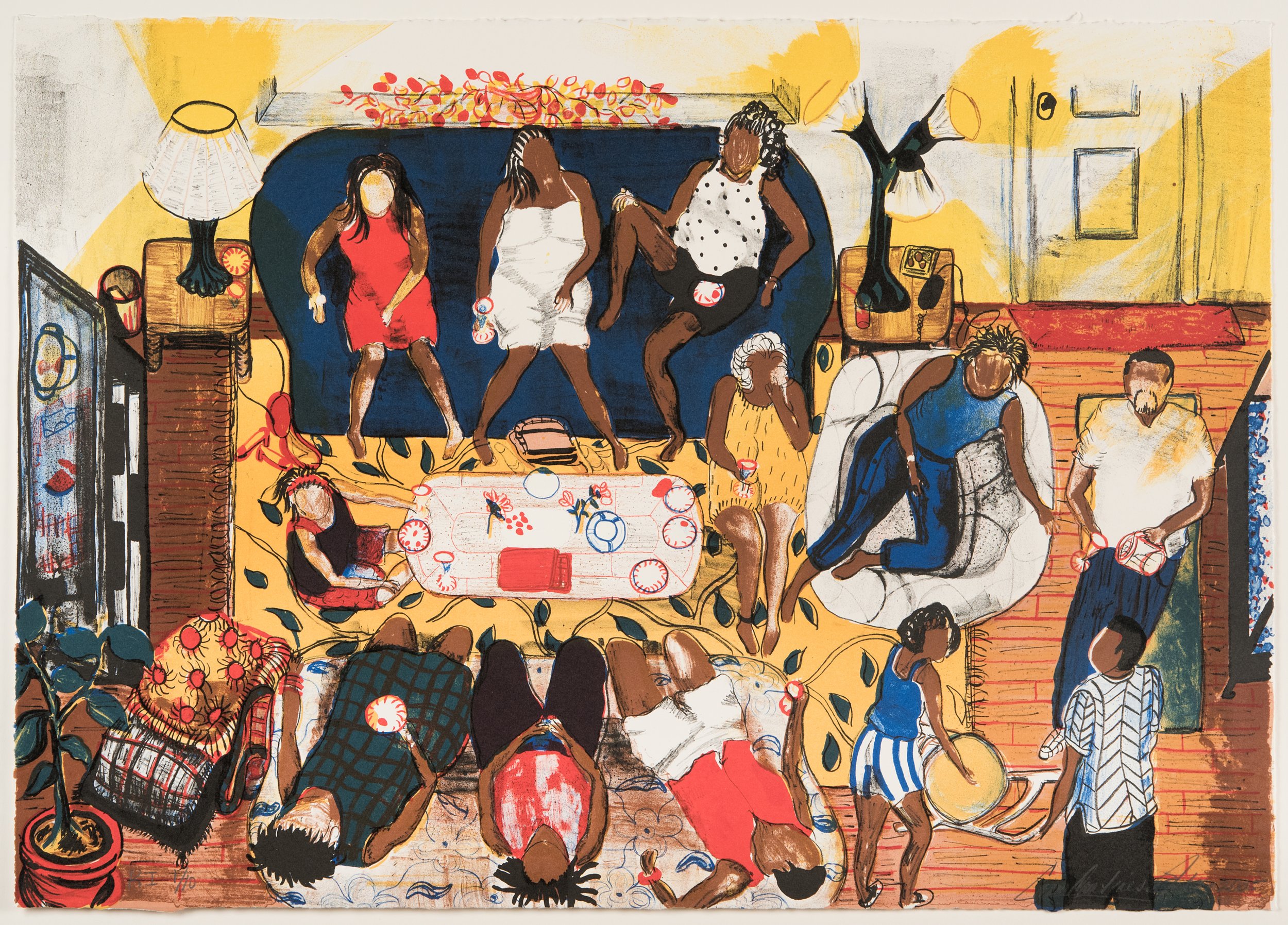

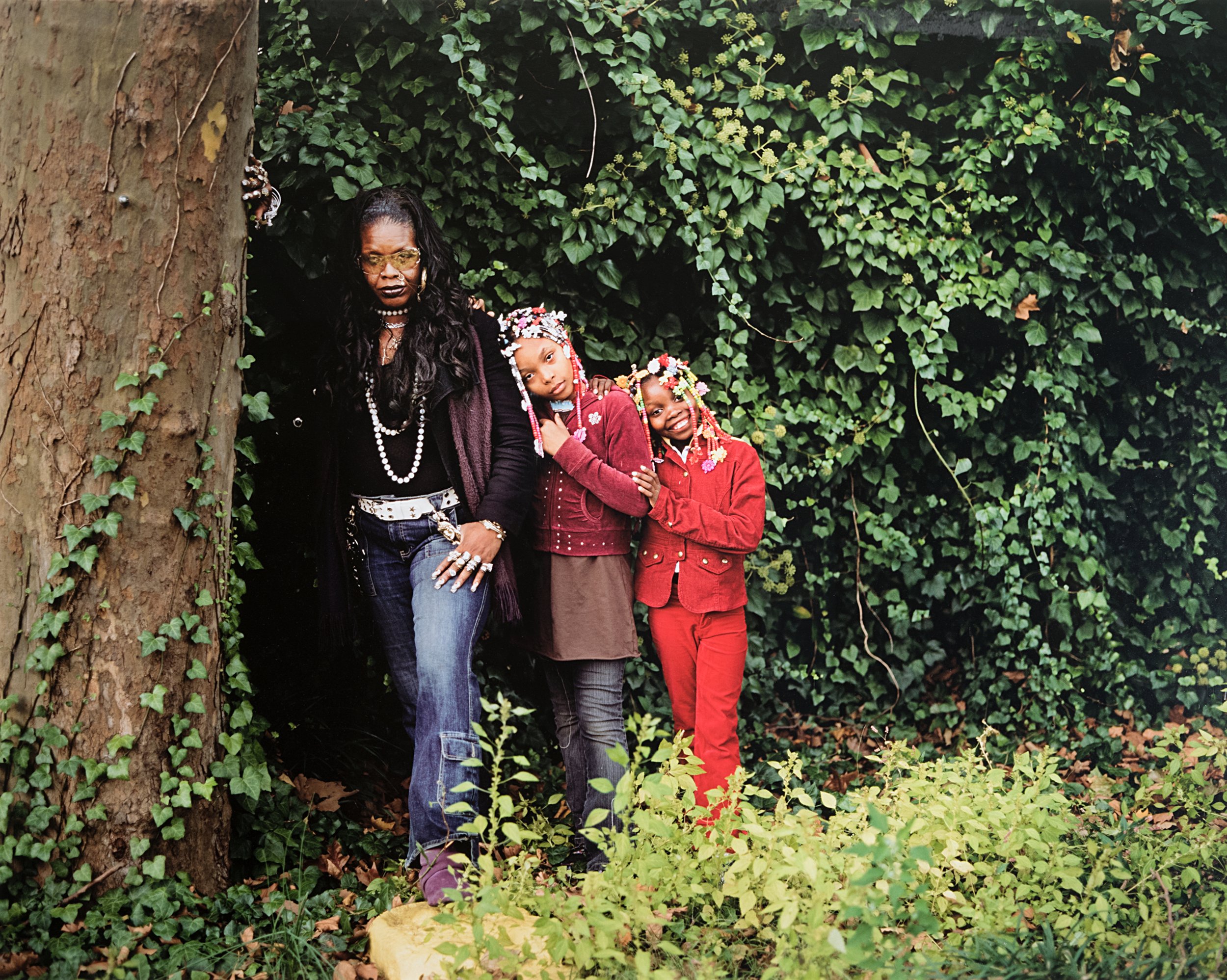

Wanda and her Daughters. Deana Lawson

Working in photography, Deana Lawson portrays a strong mother who looks as if she’s been through it all, finally getting to bask in the joys of her two adoring daughters, smiling, hair-lovingly braided with colorful flowers and beads.

“Her staged portraits [are] of everyday people – whom she views as fellow survivors of a history of slavery and colonization,” write the curators, quoting the artist as saying “They are the displaced kings and queens of the diaspora.”

“Lawson is part of a broader movement that recognizes forms of beauty that don’t conform to Western conventions, often narrowly defined by race and gender,” reads the label.

Ever wonder how Kehinde Wiley paints his enormous canvases of richly patterned settings populated by strong and beautiful Black bodies in poses that reference European Old Master paintings? Here, an oil wash study breaks it down. It is Wiley’s intention “to use the Black body in my work to counter the absence of that body in museum spaces throughout the world.”

So, how did the Montclair Art Museum get to have such an impressive collection of Black art? Chief Curator Gail Stavitsky has been at the museum for three decades, and a great deal of the collecting happened under her tenure.

“It is a collaborative effort so I must give credit to others, especially prior museum directors Ellen Harris, Patterson Sims, and Lora Urbanelli, as well as current Director Ira Wagner,” she says. “What has always guided us is the pursuit of works of art of the highest formal/visual and narrative qualities.

“The museum has been especially active in collecting and exhibiting work by Black artists during the past five years,” Stavitsky continues, citing support from the African American Cultural Committee. Stavitsky selected curators Adrienne Childs and nico okoro “for their range of expertise from historic to contemporary art. I felt that they could really complement each other and work well together and offer fresh, thoughtful perspectives on the collection.” She says she is thrilled this has proven to be the case.

With such a stellar collection, “we tried to let the works guide us,” says Childs, an independent scholar, art historian, and curator. “We also wanted to think of different ways to look at the works such as through the idea of Black Joy/Leisure and Black mythologies. We came to these categories by brainstorming and talking with each other informally.” (The other themes are Black portraiture, African diasporic consciousness, archival memory, and abstraction.)

Mother and Child. Willie Cole

“The strength of the collection was frankly a bit surprising to me,” continues Childs. “And it made the selections somewhat tough. Although we hated not to include some works, we were happy with what we decided on. It was also important to showcase works that had never been seen before and works by artists who were lesser known.”

“We were drawn to different themes and ideas,” says okoro, an independent arts consultant, curator, educator, and writer. “Two people can see the same set of objects and interpret them uniquely, through the lenses of our own lived experiences.

“Personally, the works in Black Joy and Leisure really strike a chord,” continues okoro, “as they provide an important counternarrative to the dominant narrative that traffics in Black pain and suffering. It was refreshing to see MAM’s commitment to acquiring works that depict us thriving and at rest.”

There are plenty of works that address that Black pain too, such as Sanford Biggers’ and Melvin Edwards’ sculpture. Biggers dips wooden African statues in wax, then has them shot at with firearms to honor and memorialize victims of police violence. He casts what remains in bronze to combat the amnesia that can follow acts of violence.

Edwards’ metal assemblages are reminders of lynchings, enslavement, and confinement: a lock, a chain, a hood, and scissors. “What I am doing is taking fragments of the intensity of a lynching, turning it around, changing it into an object [that is] creative and positive.”

Willie Cole responds to the matriarchy of domestic workers in which he grew up and that still surrounds him. Known for depicting the iron as a symbol for this, here he has one at a gargantuan scale, made from rusted and bent metal ironing boards; and a woodblock print made from irons and ironing boards that evokes the blueprint of a slave ship, carrying enslaved Africans to American during the Middle Passage.

Testimony. Kara Walker

One powerful work that calls out across the room is Lisa Corinne Davis’s “Essential Traits #!,” in which she has taken the pages of a 1903 American history textbook, spread them out on an enormous canvas, and embellished the original illustrations of white men with her own drawings of people of color. She wrote over the text in white ink to highlight the histories of people and events that were left out. A layer of encaustic wax provides a skin-like film to seal the work, encasing it in history.

Jacob Lawrence, Kara Walker, Chakaia Booker, Nice Cave, Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Beauford Delaney, Sam Gilliam, Julie Mehretu – there’s so much to see, and the exhibition merits several visits.

Speaking of the exhibition overall, oroko says it contains “works that deepen the conversation around depictions of Blackness and the nuances of black identity over the past hundred years.

In making selections, “We considered what MAM’s existing community might be less familiar with, and which works might draw in those that have never found their way to the museum before… I would hope the community leaves having seen unfamiliar work by a familiar artist while also becoming familiar with someone previously unknown to them.”

Montclair, NJ | Through June 23, 2024

LINKS

Montclair Art Museum

Century: 100 Years of Black Art

Subscribe to our Newsletter