Grounds For Sculpture Taps Home-Grown Artist for Afrofuturist Exhibition

May 21 was the birthday of artist Clifford Ward’s late mother – she would have been 108. In his major exhibition at Grounds For Sculpture — Clifford Ward: I’ll Make Me a World, on view through January 11, 2026, he pays tribute to the woman he considers his biggest supporter.

"Miracle of the Smiling Mom 98" is a mural made up of 98 hand-painted canvases, each representing a year of her life. She had always wanted him to write a book with that title, but he fulfilled her wish in the form of expression he does best. And, with its 98 panels, it is, in its own way, a book.

In another work nearby, Ward’s mother’s name is scrambled into the text – he invites the viewer to a kind of “Where’s Waldo?” game to find it.

It’s all in the family – GFS Executive Director Gary Garrido Schneider calls the exhibition long overdue. Ward, who has had a studio on the GFS campus for nearly three decades, has always been a part of the family, says Schneider.

“Everything concerning my entire career has been established here,” says Ward. “It’s an essential part of all that I do. This is my lifeline.”

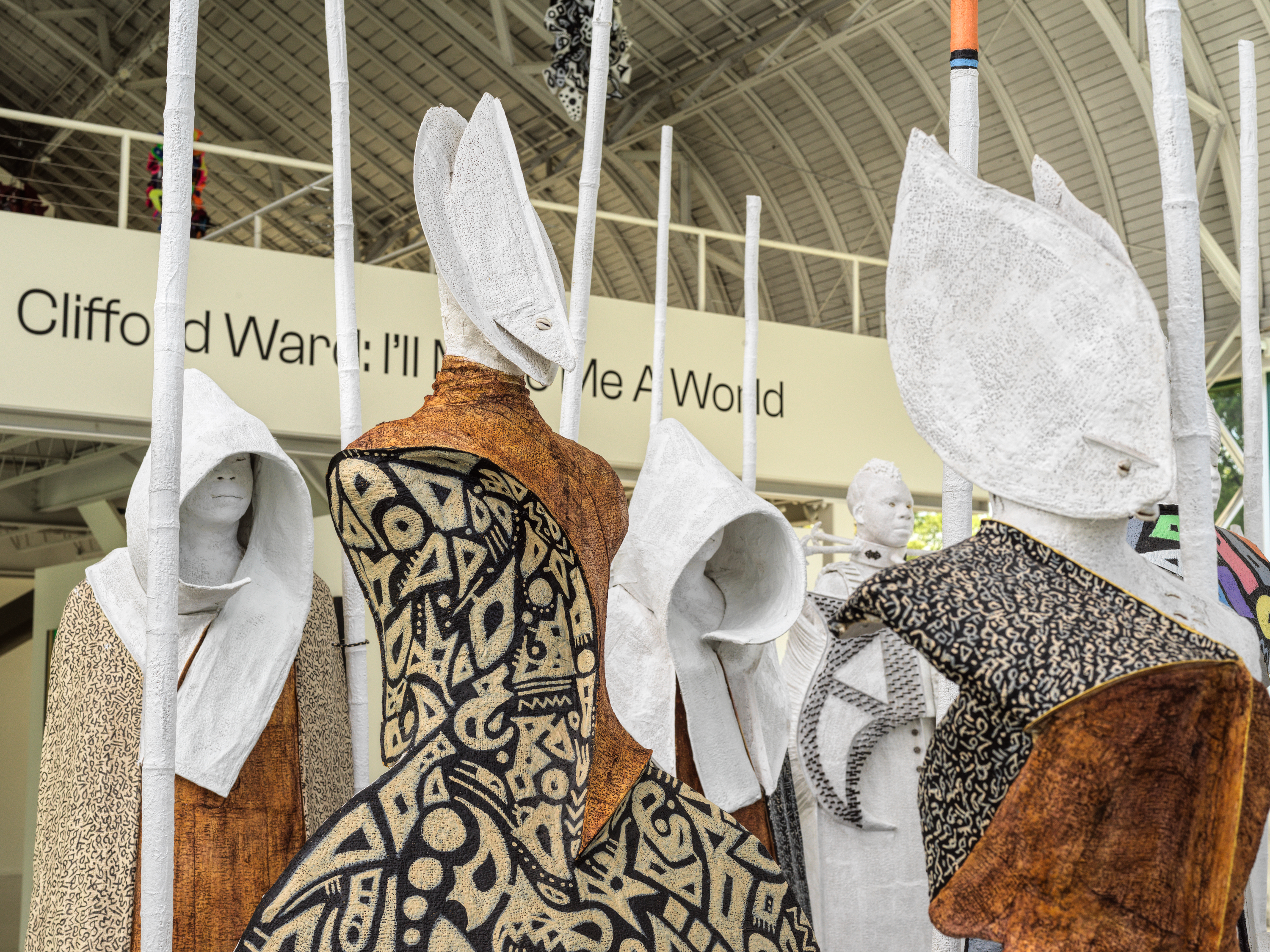

As per the exhibition title, Ward has indeed created his own world. With asemic writing – mark making that resembles written words, but with no apparent meaning – he seems to be communicating messages from another world. The pattern and texture of the marks suggest scarification. Even in his signature technique, wrapping plaster bandages over an armature, one sees marks resembling Cuneiform writing, as if spirits of another time are calling to us.

Not surprisingly, we learn that Ward is inspired by the African diaspora, Australian Aboriginal people, and Native American and Māori cultures.

Through his totemic sculptures, Ward envisions a Black future that borrows from and reinterprets the symbolism and history of the past. Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthetic with roots in the mid-20th century that weaves together science fiction, history and fantasy to explore Black experiences – the Marvel film “Black Panther” brought Afrofuturism into popular culture.

But Ward is not thinking about a genre when he creates – he’s just creating, and it’s others who apply the descriptions to his work.

Artworks Trenton exhibited a “prologue” to the GFS exhibition earlier this year. That exhibition explained how Ward developed and refined his technique, wrapping plaster bandages around a supporting armature, which is reinforced and shaped with a variety of materials, from steel, wood, and Styrofoam to cardboard and newspaper, and subsequently finished with shellac, brown wax, and acrylic paint.

"Having always felt the inclination to create, I made a significant piece one night using a long balloon wrapped around a cranberry juice jar, applied paper mâché, and painted it. This simple piece was the impetus that changed my life, leading to my becoming a professional artist,” wrote Ward. “Since then, I’ve expanded this technique to create wall reliefs and figures.”

In “The Soul’s Code,” a shroud suggests a figure, but the figure is not there. Her soul has left behind a shape, an echo.

“Animism” is a procession of 24 larger-than-life figures (6- to 9-feet tall!) cast in plaster bandages, some painted with Kente cloth patterns, that embody the Afrofuturist theme. They wear headdresses from a past or a tribal society, futuristic garments with broad shoulders, capes, wings, sgraffiti, and cowry shells. All face the big open window of the museum building, carrying spears, as if awaiting a command from their leader.

And the details! The figures are embedded with nails that form patterns of scarification, hinges, and other hardware. Paper coffee cups embedded in rows add another dimension to these white-gauzed figures, suggestive of a bustle. Glass eyes inside the forms seem to stare right at you.

But it’s not all glitz and glamour. Ward wants to remind his audiences of the horrific treatment of enslaved people, and the backs of the figures have prongs, torture devices that would snag on vegetation to keep these captive humans from running away.

A modest man in a driving cap, Ward says he’s been working on “Animism” for 12 years. He begins by making a mold of his own face. As the figures filled up his studio, he worked improvisationally, listening to the conversations of his winged messengers, griots and generals, guardians of past histories. There had been earlier opportunities to exhibit them individually but he was adamant about waiting until the series was complete.

Nearby, “King and Queen Sarcophagi” — large figures made from plaster bandage, iridescent marbles, rice paper, and lights hang from the walls — have faces that exude kindness and compassion, just like the artist’s own visage.

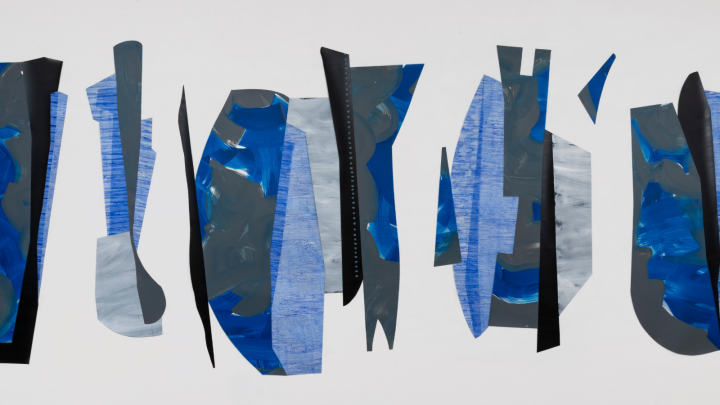

The large open space of the museum building allows everything from Ward’s “paintings” and mask-like works to forms suspended from the ceiling to be shown to their best advantage.

Ward grew up in a housing project in Jersey City, immersed in a culture that viewed Black people as barbaric, he recounted in a recent episode of State of the Arts. White saviors he saw on TV made him want to have straighter hair, lighter skin. Reading “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” changed all that. He further developed his Black identity reading James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and Langston Hughes. Now, when people identify him as African, he considers it the biggest compliment.

En route toward becoming an artist, Ward tried out different paths. He was a pre-med student (perhaps the idea of using plaster bandages first formed in his mind at that time). He earned a bachelor’s degree in speech communications at Rider University, then worked for a business and economics textbook publisher and, later, a start-up publishing company in Philadelphia. By age 40, Ward knew he had to fulfill his burning desire to make art. He studied sculpture at the Fleisher Institute in Philadelphia and began working at the Johnson Atelier Technical Institute of Sculpture in Hamilton after serving as an apprentice there in 1997-1998. He became a member of the technical teaching staff in metal chasing – metal chasing is the connecting of parts of a sculpture that are cast separately in metal.

In 2000, Ward served as part of an eight-person team at the Johnson Atelier to create a steel armature to support the famed Tyrannosaurus rex SUE's fossilized bones on display at the Field Museum in Chicago.

Fabricating other artists’ sculptures helped Ward understand how he could realize his own ideas. By 2006, he was exhibiting works like “Grace of Judith,” which was chosen as a gift for Maya Angelou at the National Constitution Center. Clifford Ward.

I’ll Make Me a World is guest curated by Noah Smalls, Director of Exhibitions and Collections Management at Williams College Museum of Art in Massachusetts. To the opening events, Smalls wore a black jacket that was unmistakably designed by Ward, with silver designs in Ward’s signature patterns. Smalls described the mark-making on Ward’s surfaces as codes, possibly spiritual or ritualistic, that refer to history, to lineage. “Clifford is communicating by bringing forth his own language. It’s mystic, but not secret. It’s beyond our scholarship and needs to be explored. By practicing close looking, you will reap the rewards. Listen to what he is saying.”