Seeking Balance in a Turbulent World with Nanette Carter

Nanette Carter has come home.

With a major career survey on view at the Montclair Art Museum through July 6, the artist, who has exhibited in Japan, Cuba, Syria, Italy, nationwide, and in this year’s Venice Biennale, has returned to her old stomping grounds.

Born in 1954, Carter grew up near MAM, taking classes, attending camp, and visiting the museum’s galleries. Her father, Matthew Carter, Montclair’s first Black mayor, was a founder of MAM’s African American Cultural Committee in the 1980s and its first Black board member.

It's also a homecoming for independent curator Mary Birmingham, formerly on staff at MAM, who grew up in Montclair at the same time as Carter (although they were in different schools — Montclair’s schools didn’t desegregate until the 1970s).

Birmingham first came across Carter’s works from the ‘70s and ‘80s in the museum’s collection while on staff, and finally got to meet the artist at her gallery, Berry Campbell, in 2022. A Question of Balance focuses on Carter’s work from the past decade: abstract large-scale collages made from cut up Mylar.

Carter initially encountered the plastic reflective material in architectural drawings in the mid-1980s. “She loved the way line looked on it and filed it away in her mind until 10 years later she began buying it in 100-foot rolls,” says Birmingham.

Since then, frosted Mylar sheets have become Carter’s medium of choice as she constructs cantilevered collages, painting and printing directly onto irregular shapes cut from the material. With Mylar, she can not only explore color, texture, and composition but also build forms incorporating balance, weight, and gravity. She uses oil paint and oil sticks on the Mylar, creating intricate textures.

In an essay in the comprehensive exhibition catalog for Nanette Carter: A Question of Balance, Kimberli Gant, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Brooklyn Museum, calls Carter a world builder. “Her abstract installations are her way of making sense of the intricacies and complexities of the environment and the human condition.

“Living in an imbalanced society,” continues Gant, “she uses universal symbols and shapes to create nonfigurative structures and environments that have the potential to be in balance and to function as portals to new imaginative possibilities.”

“The idea of bringing elements together to build a structure has fascinated me for some time,” Carter says in her catalog essay. “When I’m in the studio… I feel like I am building a structure the way a contractor would construct a building. I work on the floor, the wall, and at a large table to create surfaces that will be assembled — or as I like to say, engineered — to form a work of art. Each section comprises surfaces that I have painted, drawn or printed on. Each distinct part is essential to the finished product.”

At the entry to the exhibition is a short video made by Carter, “The Weight,” accompanied by her own voice, humming. Intervals of poetry – white words on a black ground — separate cadences of video showing the artist building her forms, beginning with the words: “Child of the fifties/ At a slower pace/ Sun days families gathered/ Church, meals and conversation.” We see a rear view of Carter with one of her cantilevered Mylar constructions adhered to the wall, as if she is holding it up, balancing it. Throughout the video, the construction is built up, with more poetry about the challenges of life: ballooning mortgage rates, the weight of wars, of class and race wars. The figure tries to balance it all, even employing a foot to elevate an errant element.

Carter creates her work directly on the wall, working in her West Harlem studio or, for especially large works, at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she was a professor for 21 years (she retired in 2021).

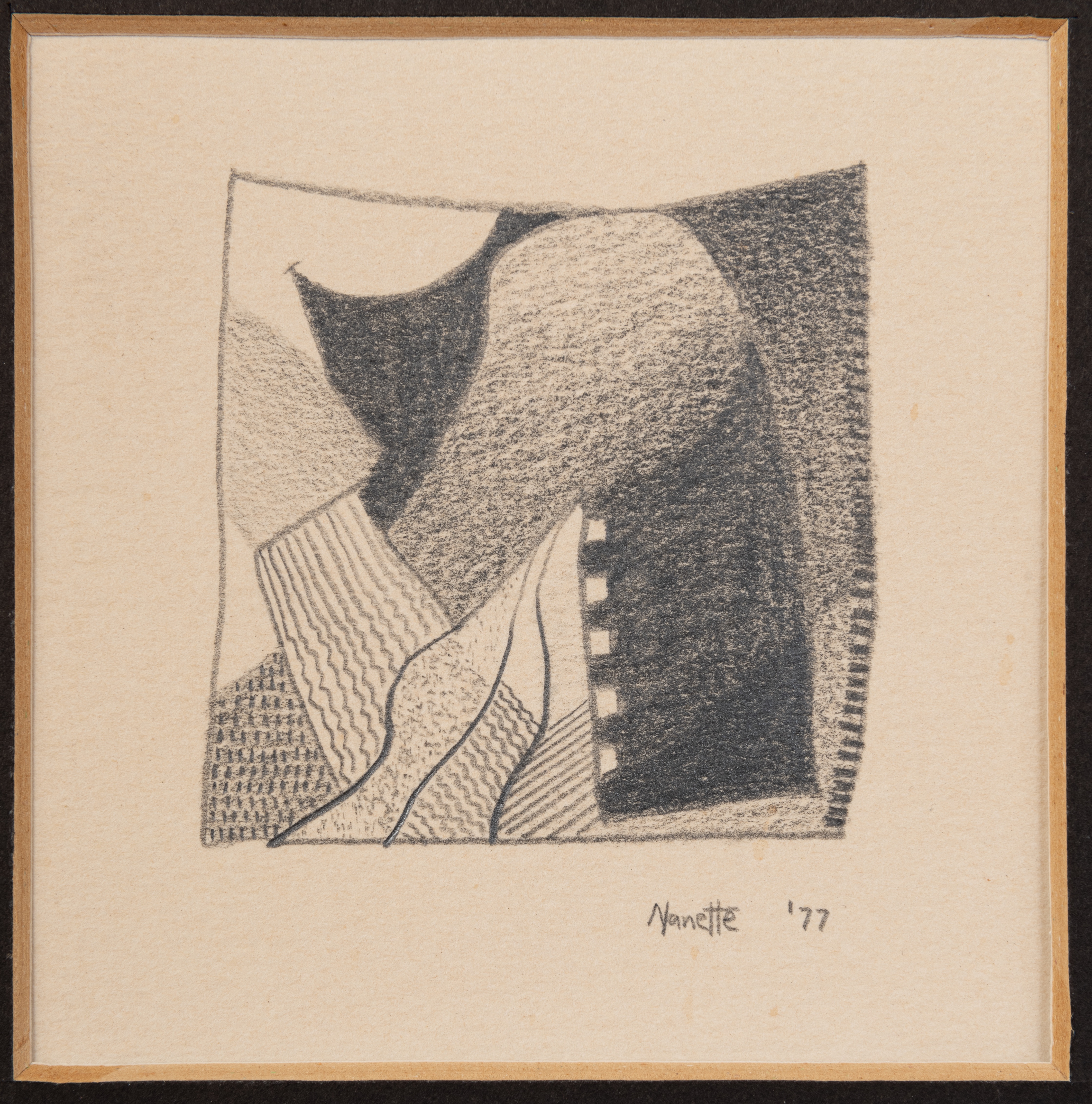

While focused on the Mylars, A Question of Balance includes a sampling of Carter’s works from the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s “to show the seeds of what she’s doing now,” says Birmingham. Even a tiny pencil drawing of a still life from her high school years shows shapes that play on the theme of balance, as does a painting of an abstracted egg in a bowl set in a field of grass.

Growing up, Carter’s parents supported her artistic pursuits. Her mother taught reading as well as ballet, tap and modern dance, choreographed productions, and created costumes for the recitals. Carter traces her process of cutting pieces of Mylar back to observing her mother cutting colorful tulle from sewing patterns. “Watching her enjoying the process is what originally drew me to making art.”

Her mother went on to become a vice principal in Paterson. “The family lived in a middle-class Black neighborhood, where the artist grew up with a sense of comfort and security,” writes Birmingham. Carter felt she was getting the love and attention “in this wonderful community of concerned Black folks… the world was my oyster.” She felt empowered to do anything to which she aspired.

Carter credits the Montclair public schools for its art education. “In the 1960s and 1970s, Montclair had stellar programs for the arts,” Carter writes in the catalog essay. “By the time I was in fifth and sixth grade, I was creating stenciled and linoleum prints and dry point etchings..” In high school she studied oil painting, etching, clay sculpture, silkscreen, ceramic, and darkroom photography, and it opened her to the possibility of a career in interior design or architecture. During the summer before her senior year, she studied art in Italy.

As a student at Oberlin in the 1970s, Carter focused on printmaking, then went on to earn an MFA in printmaking from Pratt.

The Carter family had a vacation home in Sag Harbor. There, Carter was thrilled to meet a Black artist working in collage. During the summer of 1977, working at a museum and performing arts center in East Hampton, she met the artist Al Loving, the first African American artist to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum. He became an important friend and mentor and connected her to a network of African American artists known as the Eastville Artists. This led to exhibition opportunities on Long Island’s East End.

From that experience, Carter grew her connections, meeting artists Howardena Pindell, Emma Amos, Jack Whitten, and others.

In 1984, she went to Rio de Janeiro, where she was struck by the vibrating sounds of music and drumming. “She discovered that enslaved people were treated differently in Brazil,” says Birmingham. “They weren’t disconnected from their culture, from drumming. It felt like a staccato beat” that Carter has incorporated in her work, such as forms that look like black and white piano keys.

“She listens to jazz while working, such as Fats Waller’s ‘Jitterbug Waltz,’” says Birmingham. In a work titled “3/4 time,” she cut up her etchings and recomposed them onto three panels, letting the forms dance off the edges.

“The brilliant musician and composer Wynton Marsalis has spoken about jazz ensembles as democratic collages of individuals who have banded together to perform a work,” Carter says in the catalog.

A highlight of the exhibition is the monumental “Afro Sentinels III,” an installation of abstract warrior figures Carter created to combat racial injustice and protect all people of color. “She had a vision of a series of guardians for Black and brown people, with abstract themes that reflect the times,” says Birmingham. “Ever since the Obama years, societal threats against people of color have been a concern. She was inspired by the Chinese tomb guardian figures.”

Due to its size (8-by-33 feet), Carter used a studio at Pratt to set it up while working on it. She has fine-tuned a technique of transferring her work, adhered to the wall, from one site to another.

Carter choreographs the sentinels into a linear formation, as if the figures are part of a parade or a procession. All the elements Carter has been working on up to this point in her career seem to come together in “Afro Sentinels III.”

“She’s also a news junkie, absorbing and responding to the zeitgeist,” says Birmingham.

“I like to think of myself as a chronicler of our time,” writes Carter, “dealing not only with local occurrences but also with more universal events such as wars and pandemics; women’s issues; and the theme of hope.”