Believing in Bright Colors and Angels Gets Artist Freda Williams through the Atrocities

As soon as the banner announcing the retrospective of Freda Williams hung from the red brick façade of Artworks Trenton, the excitement began. “She has so many stories to tell,” Artistic Director Addison Vincent said of the 86-year-old artist who has lived all but the first five years of her life in Greater Trenton.

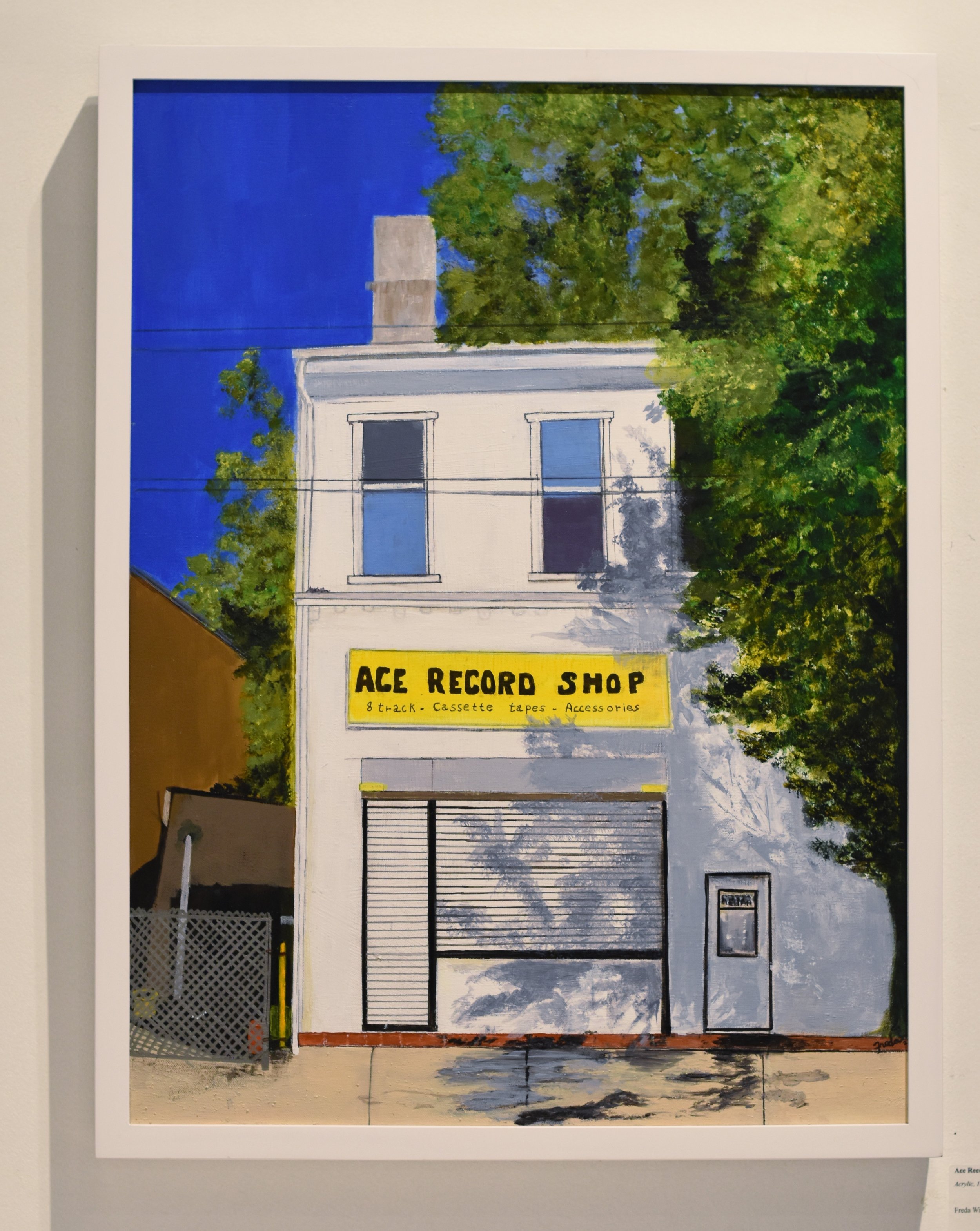

The painting featured on the banner – “Ace Record Shop” – is like a reflection of the capital city itself. The iconic storefront, painted a bright white, has been closed for more than a decade, but it’s as if it’s still breathing with memories of better times. Its yellow sign still calls out. Mature trees cast shadows on the aluminum-shuttered building, showing how it is rooted in its spot.

“Ace was loved by generations,” says Williams. “I went there during my high school years to buy 45s, and my daughter bought cassette tapes there.”

There’s something about Williams’ subjects that rings familiar, even if you’ve never been to the places she paints. When Artworks Director C.A. Shofed first visited her studio, “it felt like we’d grown up together,” he says.

Williams arrives at the gallery dressed in a tangerine-colored coat that evokes the one made famous by inaugural poet Amanda Gorman. When Williams peels off her outer later, her African-print top continues to sing about color.

“She’s always glamorously dressed,” says Vincent, who has known Williams for nearly a decade. Vincent, celebrating 10 years in his role, recalls meeting Williams at the first annual Red Dot fundraiser he curated. “I fell in love with her cityscapes. Ever since I have been a Freda fan.”

Among friends – and she has many -- Williams is a beloved raconteur. “It was her storytelling that really pulled together the eclectic works,” says Vincent, discussing the challenges of arranging subject matter thematically. “Each (of the more than 100 works) is as strong as the next, and the entire body is, in essence, pure Freda.”

“Don’t you just love to be surrounded by your own art,” says Williams with a chuckle, taking in the space around her. “This has come at a time in my life when I needed it.”

Artist Khalilah Sabree stops by. Sabree, who has a studio at Artworks and is in a two-woman exhibition at the Princeton University’s Art@Bainbridge, has also known Williams for a decade. Along with Williams’ daughter, Charlotte, the threesome would visit exhibits and share reflections.

“Over the years, our relationship has deepened, especially in the face of the loss of Charlotte (who died in spring 2022),” says Sabree. “In these challenging times, we've become pillars of support for each other, encouraging persistence in our personal and artistic pursuits.”

“Charlotte was always by Freda’s side,” says artist Kathleen Hurley Liao, who has exhibited alongside Williams and collects her work, including “Harlem Return,” on view here.

Both Sabree and Liao thrive on deep conversations with Williams in which she shares insights and experience with Civil Rights, Gullah-Geechee culture, and jazz.

“Freda's commitment to her craft goes beyond the canvas; it reflects a deep connection to her roots and a sincere desire to convey the essence of her cultural identity,” says Sabree. “She is a gem in Mercer County, and I am honored to call her my friend.”

Williams, in turn, considers Sabree a mentor. “I learned so much from her, and she encourages me.” (Sabree, too, has loaned works from her collection to the exhibition.)

Though self-taught as an artist, Williams says she doesn’t like to be pigeon-holed. She defines talent as something that is “God-given; just because you studied art doesn’t make you an artist. It’s not about an academic degree, it’s about expressing how you feel. We’ve all been given a gift and we have a responsibility to use it.

“I always wanted to paint,” continues Williams, “but I didn’t know I was what was called an artist.”

Williams has given many of her paintings as gifts. She tells a story about her first sale. During football season, when her husband was alive, Williams would escape to the basement and paint. Her husband took some of those paintings to his office, and Williams was astonished when he phoned her to say someone wanted to buy one.

Although she sang in her church choir with Tom Molloy – known as Trenton’s “artist laureate” – and collects Molloy’s work, Williams says she was not influenced by the watercolorist, known for his portraits of the city. “I admire his work, but I paint for my own fulfillment, just as people knit or crochet.

“Don’t you love to express yourself with paint?” Williams continues. “The opportunity to make visual what you’ve experienced.”

And her experiences go deep. Mabel “Freda” Williams left North Carolina with her parents during the Great Migration when she was 5. She is the youngest of five children, and her older brothers remained in North Carolina. The family would make return visits down South, where Freda’s brothers had large families. They would have cookouts and decorate with Christmas lights, creating a stage on which to perform.

Williams’ mother was a seamstress who made quilts for each of her children. “Quilting is the way our ancestors told stories of their lives. The colors included pathways to freedom, guidance to escape, just as drumming did.”

“Quilting Hands” is a painting in homage to that history. Nearby is a painting of a woman in her shop on Sapelo Island, Georgia, weaving a basket from sweetgrass. She is the weaver who created the basket used in President Obama’s inaugural parade, Williams says.

“Dock’s Truck” is a rendering of a 50-year-old vehicle, once her brother’s and now owned by a nephew, its layers of peeling paint echoed in the rich textures of Williams’ paint application. Even the frame enforces the beauty of aging paint on metal. That framing, as well as many in the show, are by Kristen Birdsey at Jerry’s Artarama in nearby Lawrence. “Charlotte used to call Jerry’s my candy story,” recollects Williams. “Kristen understands what I’m trying to say and makes wonderful suggestions.”

Williams, who attends United Methodist Church, was sent to Catholic school as a child. “My mother told them she wanted me to receive their education but not their religion,” she says. She studied business administration at Rider College (now University) and worked in the steel industry as manager of employment for 20 years, and then 25 years as manager of Affirmative Action with the State Department of Education. In 2012 she retired and began making art full-time.

In 2015, Freda, Charlotte, and photographer Sarita Wilson took a trip to Georgia and North Carolina, exploring the history of Gullah Geechee (descendants of West and Central Africans who were enslaved and bought to the lower Atlantic states of North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, and Georgia to work on the coastal rice, Sea Island cotton and indigo plantations) for a collaboration. Charlotte, who worked as assistant chief of investigations for the officer of the public defender, also made fused glass art, having studied with Judy Tyndall at Artworks. Their joint project was exhibited at Trenton’s Smith Family Foundation, an organization fostering education and empowerment. Several of those works can be seen at Artworks, such as paintings on Jekyll and St. Simon’s islands. In one, we see “the footprints of younger people who wanted a taste of the mainland. They thought it was a better place, and ignored the pleas of their ancestors to hold on to their culture.”

“I’m still learning the history of my ancestors who were kidnapped and enslaved in Charleston and Jekyll Island,” Williams says. Going to those islands in Georgia, she was emotionally moved. “I was in the place where my ancestors were brought in chains. I’m standing at the point where the slave ships docked.” She brought back sand from the beaches and has incorporated it in paintings of the region.

Although Williams hasn’t been to Brazil, she likes to paint its favelas. “Even though the people are oppressed, they hold on to brightness. They see color – you have to see brightness in order to survive, you can’t dwell on darkness.” Children are depicted flying kites from the rooftops, and candy-colored clothes hang to dry.

During the worst of the Covid 19 pandemic, Williams tried to hold on to that view. “I vented my feelings on canvas when number 45 – I can’t say his name – did not provide help to Black and brown people in cities. Attention was not given to the people putting their lives at risk – I call them essential angels.”

“Confidence” is a painting of a broad-shouldered African American woman “because you’ve got to have faith that this evil will not continue.”

Williams likes to paint her reflections of the Harlem Renaissance. “It was a time when African Americans were thriving in the arts – Langston Hughes, Nina Simone.” It should be mentioned that the jazz playing in the gallery is from a playlist Vincent compiled from Williams’ suggestions.

Williams is a firm believer in angels. Forty or so years ago, when her husband suffered a fatal heart attack at the wheel of the car – Williams was in the passenger seat – a man came out of nowhere and grabbed the steering wheel, safely righting the vehicle. “He disappeared,” Williams recollects. “I never saw him again. I don’t know who he was. Angels have helped me with my grief. They come into your life when you need them, like Addison, calling and inviting me to do a retrospective.”

Trenton, NJ | Through March 16, 2024